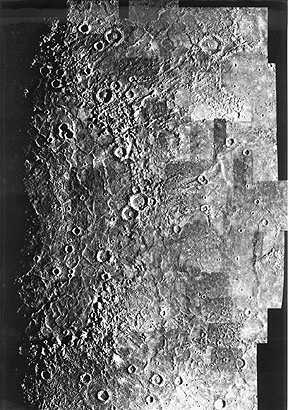

November 3, 1973 first to Venus (see below) and then past Mercury on March 29, 1974 and around the Sun to return for another Mercury flyby in September 1974. The two encounters permitted 55% of the planet to be imaged. Craters, once again, are the prevalent geomorphic feature, with some impact basins exceeding 200 km (124 miles) (largest is Caloris at 1300 km [807 miles]).

Unlike the Moon, basalt-filled maria are absent, although some small darker patches have been seen. This implies that the second melting that occurred on the Moon about 3.8 billion years ago did not happen on Mercury whose surface probably is even older and preserves the same period of impact devastation associated with the lunar highlands.

Venus is another matter, with a complex younger surface and an intriguing history. Its high reflectivity (as evidenced by the bright "Evening Star" easily seen from Earth) implies a dense shrouding atmosphere, so that knowledge of its surface would depend either on landers or on cloud-penetrating radar. A series of missions by both the U.S. and the Soviet Union have done these things and unlocked some of its mysteries.

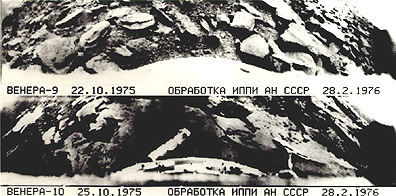

Exploration of Venus by flyby probes was part of NASA's Mariner program which also included trips to Mars and the above-mentioned Mercury passes. Mariner 2, with its infrared and microwave radiometers, was the first American interplanetary probe, launched on August 27, 1962. Passing Venus as close as 41,000 km (25460 miles), it determined an approximate temperature for the outer cloud deck of ~500° C. Mariner 5, in 1967, came within 10,150 km (6300 miles), using these and a UV sensor to add more to the database. About this time, the first Soviet probe, Venera 4, descended by parachute through the atmosphere in an attempt to touch down on the surface. It apparently was crushed by the dense atmosphere (~90 atm) and high temperatures but did return information confirming that CO2 makes up about 97% of all gases present (very little water) and detecting droplets of sulphuric acid in the outer cloud deck. After two more failures, Venera 7 reached the surface and survived for 23 minutes in 1970. Venera 8 also succeeded in 1972, adding chemical composition data on radioactive U, Th, and K from analysis by a gamma ray spectrometer that suggests local rocks are potassium-rich basalts. Measured surface temperatures were ~470° C. Four more Veneras reached the surface between 1975 and 1982; each carried a photographic system that returned pictures of the immediate surroundings. Two views, taken from Venera 9 and 10, disclose a rocky surface; note in the upper image a distinctive rock that reminds some viewers of a MacDonald's hamburger.

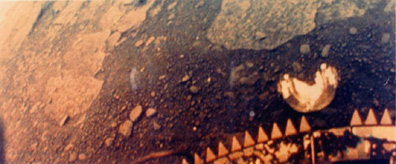

A view in color from Venera 13 suggests an iron-rich oxidized surface:

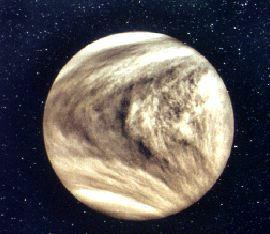

The next U.S. probe to Venus was Mariner 10, arriving in February 1974. Using a special UV filter, its imaging camera was able to penetrate the CO2-dominated atmosphere to detect cloud swirls that emphasized concentrations of excited carbon monoxide, suitable as markers of the general circulation patterns (winds up to 370 km/hr [230 mph] within the gas envelope).

Two Pioneer Venus spacecraft arrived at the planet in December 1978 and were placed into orbit; Pioneer Venus 2 deployed a landing probe that survived for about an hour. They operated mass and ultraviolet spectrometers, an infrared radiometer, and a radar altimeter to profile-map the surface tracks over which they passed, leading to a topographic map (100 m [305 ft] vertical accuracy) covering more than 90% of the planet.

The inpenetrable cloud cover masking Venus was first penetrated by Earth-based imaging radar beams sent from antennae at the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico, the Goldstone Tracking Station in California, Haystack in Massachusetts, and others. Wavelengths vary from 3.8 to 70 centimeters. Interference techniques using Doppler shifts process the reflected signals which offer some information on dielectric constants, surface roughness, slopes and rather crude estimates of elevation differences. Surface resolutions (areal) can be as low as 100 km (62 miles) or can be better than 3 km (2 miles). Here is an image showing variations in intensity of a backscattered radar beam transmitted to Venus at 12.5 cm from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory's Goldstone Tracking Station in the Mojave desert.

Even these earlier radar images pointed to a relatively flat Venus but with some highlands exceeding 6 km (3.7 miles). The Soviet Venera 15 and 16 (1983) carried imaging radar (8 cm wavelength) capable of 1-2 km (0.6-1.2 miles) ground resolution that gathered coverage over about 25% of the planet. The scene below is in the general Ishtar Terra region of northern Venus and shows the eastern part of Laksmi Planum, the wrinkled Maxwell Montes, and the large crater Cleopatra, a scene well over 2000 km (1240 miles) wide at the base.

Code 935, Goddard Space Flight Center, NASA

Written by: Nicholas M. Short, Sr. email: nmshort@epix.net

and

Jon Robinson email: Jon.W.Robinson.1@gsfc.nasa.gov

Webmaster: Bill Dickinson Jr. email: rstwebmaster@gsti.com

Web Production: Christiane Robinson, Terri Ho and Nannette Fekete

Updated: 1999.03.15.