Galileo was programmed to transit close to two asteroids. The first, Gaspra, was passed in 1991. This asteroid, 19 x 12 x 11 km (~12 x 7.5 x 7 miles) in size, is composed of iron-nickel and Fe-Mg rich silicates. This is how it appears in color:

The second, Ida, was approached and imaged on August 28, 1993, as seen here (at about 33 m (107 ft) resolution:

This asteroid, about 58 x 23 km (36 x 14 miles) in dimensions, is chondritic and, like Ida, pockmarked with craters. Totally unexpected was the presence of a small orbiting body, about 1.5 by 1.2 km, that was named Dactyl - making this pair the first known binary asteroids. Close-up, Dactyl itself has a small crater, making it look a bit like Saturn's Mimas in miniature:

The next visit to the asteroid belt will be made by NEAR, for Near Earth Asteroid Rendevous mission, launched in early 1996 to reach the large asteroid Eros in January, 1999.

Asteroids, and fragments therefrom, occasionally hit the Earth, as we saw in Section 18 dealing with impact craters. So do comets: a possible example was the 1908 Tunguska event in Siberia where trees were knocked down over hundreds of square kilometers by an explosion just above the surface which also caused great amounts of dust to be carried into the atmosphere, producing abnormal red sunsets worldwide for the next several years. Comets are among the most spectacular of the heavenly bodies, having been given mystical significance until their true nature was determined.

It is now known that comets are mainly ice balls of varying sizes (up to 10-30 km [6-18 miles]), mixed with rock debris to some extent, that travel in eccentric orbits (e.g., Kuiper belt) from within the solar system leading to repeat appearances or simply may fly through once if not captured gravitationally. As a comet passes the Sun, solar wind and other factors cause it to ablate, with materials collecting both as the coma (a glowing ball which can reach from 10000 to 100000 km [6200-62000 miles] in apparent diameter) around the solid nucleus and trailing off as a long tail (up to 100 million km (62,000,00 miles) in length) of dust and plasma that points away from the Sun along a line vectored to it. The coma and tail are visible because of reflected sunlight; the particles also fluoresce by UV activation. The nucleus ("dirty snowball") is thought to be composed of very primitive materials organized during the solar system's development. Spectroscopic studies indicate presence of molecular compounds of carbon, nitrogen, and hydrogen, including CN, NH, NH2, and HCN, which break into ions carried into the tail. The number of comets - most still undetected - within the Solar System may number in the millions.

The orbits of some comets are well enough defined (through observations) to predict when individuals will return. Most comets come from either the Kuiper Belt beyond Pluto or the vast Oort "Clouds" that extend to the outer reaches of the solar system; some may be intergalatic. The best known of all comets is Halley whose presence was first recorded in ancient times. Its periodicity, first predicted by Edmund Halley as a verification of Newton's Laws of Motion, leads to a reappearance about once every 76 (range 75 to 79) years. Having shown up in 1909, as seen in this wide angle view that displays its magnificent tail, it was expected again in 1986 and was predicted to put on a great celesial display (which generally "fizzled").

Debate raged in advance about sending one or more space probes to examine it close-up, since next opportunity would not be until 2061. Although NASA decided against this adventure, Japan, the Soviet Union, and the European Space Agency sent probes to gather data; in particular, the Italian government designed and launched a spacecraft named Giotto which came within 540 km of the nucleus on March 13, 1986. Here is a close approach view:

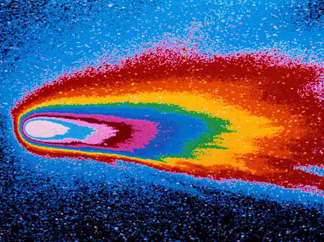

Halley's nucleus, measured at 16 x 8 km (10 x 5 miles), was found to be very dark, lumpy and of low density (0.1 - 0.2 g/cc). This suggests that it was then very porous, with most of the ice having ablated or evaporated away, leaving carbon-rich dust as a residue. Although not as bright as anticipated and a disappointment to ground viewers, the comet seen through telescopes provided exceptional displays. Variations in coma and tail reflectivity, representing particle density differences, can be emphasized by displaying these in false color:

The latest comet sensation is Comet Hale-Boggs, discovered on July 23, 1995, that passed Earth as close as 85 million miles on April 2, 1997. Hailed by many as the Comet of the Century because of its size (4 times larger than Halley) and brightness, it was visible in both northern and southern hemispheres during much of the first half of 1997. Here is a typical view, taken on March 11, 1997 by Jerry Platt, one of many amateur astronomers who have tracked this spectacular celestial visitor.

So far, almost 900 comets have been discovered through telescope searches. Most positioned well away from the Sun are without pronounced tails, and are best found by looking for notable displacements of small bright objects (early stage comas) relative to fixed star backgrounds in film records taken days apart. Such motions delineate the advance of comets, as well as reflecting asteroids, at high speeds through solar space.

Code 935, Goddard Space Flight Center, NASA

Written by: Nicholas M. Short, Sr. email: nmshort@epix.net

and

Jon Robinson email: Jon.W.Robinson.1@gsfc.nasa.gov

Webmaster: Bill Dickinson Jr. email: rstwebmaster@gsti.com

Web Production: Christiane Robinson, Terri Ho and Nannette Fekete

Updated: 1999.03.15.