A plethora of spectacular surface images have built up from the Mariner 9 and Viking missions. Only a few, to whet your intellectual "appetite", will be shown below but for the curious, consult these two references for many more pictures: The Geology of Mars, T.A. Mutch et al., 1976, Princeton University Press and Viking Orbiter Views of Mars, C. R. Spitzer, Ed., 1980, NASA SP-441.

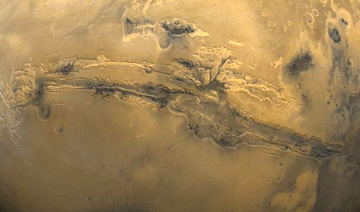

We start first with probably the greatest "hole in the ground" ever discovered in the solar system. Look at this Viking color mosaic extracted from the near hemisphere view you looked at earlier, here centered on the most conspicuous feature on Mars: the Valles Marineris which extends up to nearly 4000 km (2480 miles) (close to the entire width of the 48 contiguous United States) and attains depths between

2 and 7 km (1.25 - 4.35 miles). The canyon is actually a series of structural troughs produced by faulting radial to the Tharsis bulge to the northwest, rising some 11 km above the surrounding plains, on which are the three dark shield volcanoes (each about 10 km in height above the bulge), named on the preceding page. A look inside the canyon wall, along a segment called South Candor Chasma, conveys the sense of steep slopes, perhaps furrowed by water erosion, and basal landslide deposits.

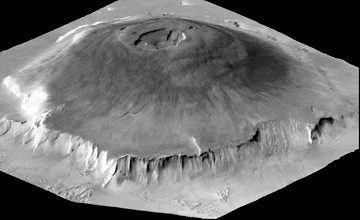

From Mariner 9, and later from Viking, the large structure known as Olympus Mons in the Tharsis region is shown below (top) to be a huge shield volcano (now dormant) - many times the area and volume of the big island of Hawaii, itself built up of basaltic outflows from several major vents. Olympus has a median diameter of 625 km (375 miles) and a height up to 25 km (16 miles). Its elliptical central caldera is 80 km (50 miles) in major axis; it is surrounded by a cliff 7 km (4.3 miles) high which stands out in the perspective view (bottom) derived by combining an image with topographic data. The origin of this cliff is still being debated, but some scientists cite it as evidence of an escarpment resulting from wave erosion by an ancient (now vanished) ocean that may have covered at least part of Mars. Note the distinctive grooved terrain (volcanic origin?) beyond the volcano's edge.

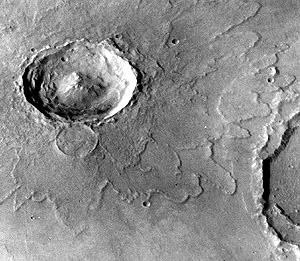

Extensive impact cratering was observed by Mariner 4, which sent back the first ever images (21 all told) taken of another planet's surface (one seen in the top photo below) by a space probe that approached to within 9800 km (6086 miles). As imaged the next year by Mariner 6, the Sinus Sabeus region of the southern highlands (bottom) preserves typical impact craters in the ancient terrain that apparently has not been extensively resurfaced by lavas. Note that none of the larger craters in this view have central peaks. Mariner 9 and the Vikings confirmed that a large fraction of the (older) martian surface remains heavily cratered.

One can argue that this landscape has many similarities to the still cratered Earth in its early stages before extensive water had collected into major oceans. Some of the martian impact structures retain well-preserved ejecta blankets that display prominent lobes, such as seen here around the crater Yuty. The ejecta was probably fluidized by vaporization of carbon dioxide-rich ice lying just beneath the surface.

Code 935, Goddard Space Flight Center, NASA

Written by: Nicholas M. Short, Sr. email: nmshort@epix.net

and

Jon Robinson email: Jon.W.Robinson.1@gsfc.nasa.gov

Webmaster: Bill Dickinson Jr. email: rstwebmaster@gsti.com

Web Production: Christiane Robinson, Terri Ho and Nannette Fekete

Updated: 1999.03.15.