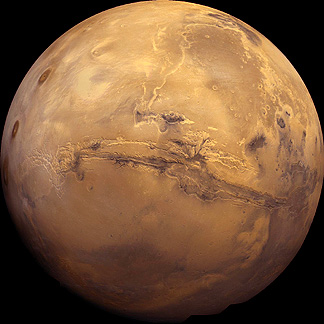

Take a look below at a beautiful full-face image of a martian hemisphere , which should make it obvious why Mars is also known as the Red Planet. This mosaic was constructed from reprocessed Viking images. Two conspicuous features, described later, are the huge gash across the face known as Valles Marineris, and the three great volcanoes in the Tharsis group, on the left.

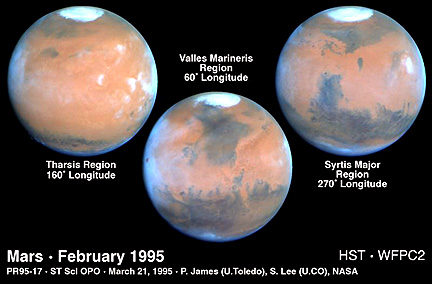

Compare this with three hemispherical views of Mars taken by the electronic camera system on the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) through filters that allow close approximations to true color. The blues along the limbs are somewhat artificial.

A great deal is now known about Mars from flybys, orbiting surveyors, and landings. The first flyby, Mariner 4, on July 14, 1965 produced 22 images covering roughly 1% of the planet. Mariners 6 and 7 passed Mars on July 31 and August 5, 1969, together obtaining 199 images that extended coverage to ~10%. A typical Mariner 6 image, shows frost-covered parts of the south polar region, with dark craters, furrows, and pits.

A quantum leap in coverage followed the first successful orbiting of another planet when Mariner 9 arrived on November 13, 1971. Returning more than 7300 panchromatic images, a wide angle TV camera capable of 1 - 3 km (0.6 - 1.8 miles) resolution mapped almost the entire surface while selected areas were imaged by a narrow angle TV camera at 100 m (328 ft) resolution. Mariner 9 also carried an IR radiometer, an IR interferometer spectrometer, and UV spectrometer. The imaged surface qualifies Mars as one of the most diverse and spectacular planetary bodies in the solar system. Lacking vegetation and water cover, the easily seen geologic features were often grandiose in scale and sometimes unique. Their interpretation by astrogeologists, which as with most extraterrestrial objects starts by comparing or contrasting with those known on Earth, often required innovative explanations.

A typical Mariner 9 view, as a mosaic, shows fractures erosion (stream?) channels, and craters.

The Russians launched Mars 2 and 3 probes to that planet in 1971 but achieved only limited data acquisition, mainly on the magnetic field. In 1973 the Soviets sent three more spacecraft to the Red Planet. In March of 1974, Mars 4 failed to orbit the planet but Mars 5 did long enough to return data, including images, during 10 of its 20 orbits. Mars 6 successfully descended through the thin martian atmosphere but failed during the last second before touchdown.

The culmination of U.S. exploration to Mars began on August 20, 1975 and September 9, 1975 with the launches of Vikings 1 and 2 respectively. Their Orbiter components were inserted around the planet in late June and early August of 1976, coinciding roughly with America's Bicentennial Celebration. Each carried two identical vidicon (TV) cameras capable of color imaging (as composites of black and white images taken through color filters) and acquiring stereo scenes at 100 m (328 ft) resolution. They also bore a thermal mapping infrared spectrometer and a second IR spectrometer designed to detect atmospheric water.

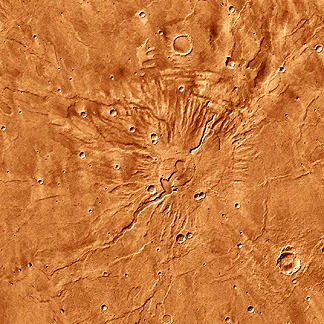

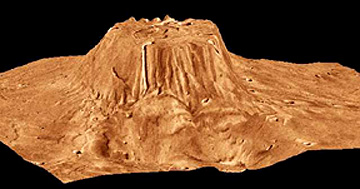

The two images below show a color version of the Volcano Tyrrhena. The first image does not give a sense of relief but when topographic information is confounded with this image, a perspective view marked by strong vertical exaggeration gives a sense of its height:

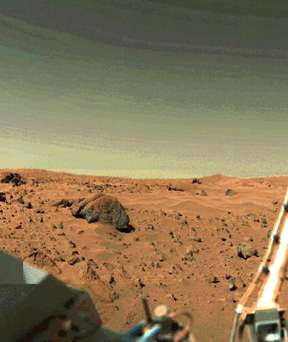

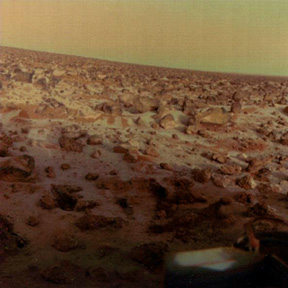

Both Vikings also transported separable landing vehicles that descended by parachute throught the atmosphere. Viking 1 Lander touched down on July 20, 1976 and 2 on September 3. Both TVs successfully transmitted surface views in color of the immediate ground up to the visible horizon.

The two Viking Landers were exceptional ground truth devices. These panoramas from Vikings 1 and 2 reveal a red iron-coated surface consisting of rocks (the largest > 2 m [6.6 ft]) mixed with sand and dust, some piled into incipient dunes. In other views, some rocks look like vesicular basalt. Note the yellow-brown tones in the lower, dusty layers of the sky's rarified gas envelope (mainly carbon dioxide). This stationary observatory was also equipped with magnets, a seismometer, an x-ray fluorescence spectrometer (that receives samples from a movable scoop), a miniature meteorological station, and 3 experiments seeking signs of metabolic action (mainly, as gases released or absorbed) by biogenic matter (none found).

Code 935, Goddard Space Flight Center, NASA

Written by: Nicholas M. Short, Sr. email: nmshort@epix.net

and

Jon Robinson email: Jon.W.Robinson.1@gsfc.nasa.gov

Webmaster: Bill Dickinson Jr. email: rstwebmaster@gsti.com

Web Production: Christiane Robinson, Terri Ho and Nannette Fekete

Updated: 1999.03.15.