A feel for what to look for, and the variations in morphologic expression owing to differences in erosional state, at a crater site can be gained by switching again to the Geological Survey of Canada's Web Page on Impact Cratering (http://gdcinfo.agg.emr.ca/crater/world_craters.html). Go to the list of individual craters and check these especially interesting sites: North America: Brent/Clearwater East and West/ Deep Bay/ New Quebec; South America: Araguainha; Africa: Aorounga/ Bosumtwi/Rotor Kamm/Vredefort; Europe: Ries; Asia: Bigach/Popigai; Australia: Henbury/Wolfe Creek.

With this practice behind you, we challenge you to find the crater

in this Landsat scene:

If you succeed in the hunt, you will have pinpointed the 6 km

(4 mile) wide Goat Paddock crater in Western Australia (click here for a closeup view [Goat Paddock2]). Interior Australia is the home of perhaps the most dramatic

exposure of the central peak of a complex crater anywhere in the

world, seen below in this aerial oblique view of a ringed mountain

at the Gosses Bluff Crater.

The 6 km (4 mile)-wide ring consists of layers of resistant sandstone

tilted at steep angles as the strata were driven upwards on end

during the rebound of the crater floor into the peak. They have

since been breached so that the lower interior now exposes softer

rocks being eroded away. In the Large Format Camera photo below, taken

from the Shuttle, this central peak stands out in sharp contrast

to the folded rocks of the McDonnel Range to its north.

The outer sections of the crater have been nearly obliterated through erosion but are faintly expressed as a dark band in the photo; field studies show the approximate diameter of the full crater to be 22 km (14 miles).

Water often fills complex craters sufficiently intact to retain

a central depression. A Seasat radar image of the Elgygytgyn Crater

in Siberia (diameter = 18 km [12 miles]) is a good example; the

aerial oblique view offers a different perspective.

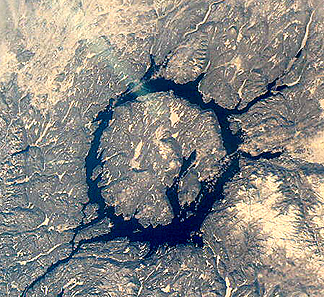

A different kind is Manicouagan, a 100 km (60+ mile) structure

in southern Quebec of Canada which has a great central peak area

of igneous and metamorphic rocks, among which are feldpar-rich

rocks in which much of the feldspar has transformed by shock into

glass, known as maskelynite. Like Manson, there is a depression or moat between peak

and (now eroded) rim that formed annular valleys which filled

with water when a hydroelectric power dam blocked the draining

rivers.

Because of this outline, astronauts journeying back from the Moon could see this crater from well out in space.

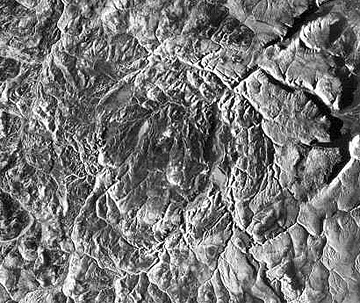

A SIR-B radar image of southern Ontario highlights two juxtaposed

but unrelated craters, that are very different in age, in size,

and in structural state.

The partially circular lake-filled structure on the right (east) is the 8 km (5 mile) wide Wanapitei crater estimated to have been formed 34 m.y. ago. The far larger Sudbury structure is evidenced by a pronounced elliptical pattern, more strongly expressed by the low hills to the north. This huge impact crater (some argue it was at least 245 km [150 miles] across when it was circular) was created about 1800 million years ago. It was subsequently deformed by the strong northwestward thrusting of the Grenville Province terrane against the Superior Province (containing Sudbury) more than 900 million years later. After Sudbury was initially excavated, magmas from deep in the crust invaded the breccia filling to emplace against its walls (some investigators think that the resulting norite rocks are actually melted target rocks). This igneous rock is host to vast deposits of nickel and copper, making this impact structure a multi-billion dollar source of ore minerals.

Radar can sharpen the appearance of an impact structure, as demonstrated

with this aerial radar image of the Haughton crater (24 km; 15miles wide) in Canada. Although about 23 million years old, much

of the crater's morphology has survived erosion.

Code 935, Goddard Space Flight Center, NASA

Written by: Nicholas M. Short, Sr. email: nmshort@epix.net

and

Jon Robinson email: Jon.W.Robinson.1@gsfc.nasa.gov

Webmaster: Bill Dickinson Jr. email: rstwebmaster@gsti.com

Web Production: Christiane Robinson, Terri Ho and Nannette Fekete

Updated: 1999.03.15.