Every American manned mission since 1962 has included a look back at the Earth by returned film photography, generally with hand-held cameras. This photography has been one of the most productive but least-known products of the American civilian space programs. This Section briefly summarizes the history and current status of such photography, focusing especially on geologically useful targets, i.e., land areas. A convenient organization will be by program, although photography is rarely more than an incidental activity on most manned missions. (Women today routinely fly on NASA missions; accordingly, euphemisms for "manned" are not necessary). Results from Soviet/Russian missions are considered here with only one example of the latter.

For the missions in general, the most readable and authoritative account is "Liftoff" (1988) by one of the astronaut participants, Michael Collins of Apollo 11 fame *. A general reference covering all of American space photography through 1989 appears in the journal Geocarto International, vol. 4, no. 1, 1989. Collections of astronaut photographs prior to those shot from the Space Shuttle are the mainstays of two books, "Space Panorama" and "The Third Planet" by the author (PDL, Jr.) *.

For readability, references will be cited "blind" by placing a blue asterisk near or next to individuals involved such that the full reference can be accessed optionally. Only the most important are listed this way; the literature on the subject is now quite large. The same approach, cited by a double asterisk (**), is followed for several tables that list photo equipment used in various missions.

Information about most of the U.S. astronaut missions, along with selected photos taken during many of these flights, can be accessed at http://images.jsc.nasa.gov (select the Press Release option button).

The beginnings of space photography can be traced to automated cameras onboard V-2 rockets fired in the mid 1940s from the White Sands Proving Grounds in New Mexico. From then through the early days of NASA, cameras were also operated on various sounding rockets and missiles. An example is this photo taken by an automatic K-12 camera, using black and white infrared film, from a Viking sounding rocket that reached a height of 227 km (140 miles). The film is then recovered from the crashed vehicle after it falls back to Earth. The scene viewed here extends southwestward across parts of New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, California, and northwest Mexico (upper Gulf of California on the left).

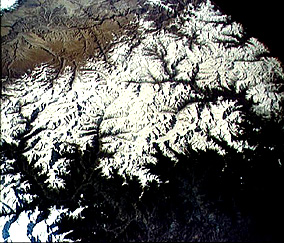

It was only in the last two missions - MA-8 and MA-9 - that systematic terrain photography was a formal experiment. The astronauts for these missions, W.M. Schirra (8) and L.G. Cooper (9) were given one 3 hour briefing by the writer, covering principles of geology, geology of the flight path, areas to be photographed, and a rock collection for study. Schirra's pictures, though taken precisely as scheduled, were largely spoiled by cloud cover over the Brazilian Shield, the only area expected to be accessible within the short flight time (6 revolutions). However, with more than 34 hours flight time, Cooper had far more opportunities to photography both pre-selected sites and targets of opportunity. The 24 excellent Hasselblad color photos he took, including these looks at the west coast of Burma (top), with its Arakan Yoma Mountains, and the Irawaddy River to the east, and the high mountains of the Himalayas (bottom), were given wide publicity, and led to subsequent terrain photography experiments on the Gemini missions.

The Gemini Program (two astronauts to a spacecraft) was a major step forward in American space capability. Intended solely as preparation for Apollo, ten manned missions were flown in 1965-65, accomplishing orbital rendezvous, extravehicular activities, tethered flight, and many scientific experiments including 70 mm terrain and weather photography. The Synoptic Terrain Photography Experiment (S005) produced some 1300 usable 70 mm color pictures of the Earth's surface. These were an enormous stimulus to orbital remote sensing, one being that they were released to the public without restriction. Among spectacular photos returned from the Gemini 4 mission is this oblique panorama showing Egypt's Nile Delta in the foreground, with the Gulf of Aqaba-Dead Sea in the background:

This picture highlights two characteristics of many of the astronaut photos: 1) they are oblique shots that often contain the Earth's horizon in the background (but sometimes the curvature is from the window of the spacecraft), and 2) there is often a blue cast that overprints the entire photo, which results from blue backscattering from the atmosphere.

The flight plan (plots of orbits) for Gemini 12 is shown in this map:

One of the key photos obtained during this mission shows Oman, the Straits of Hormuz, the Persian Gulf, and part of the Zagros Mountains of Iran.

Code 935, Goddard Space Flight Center, NASA

Written by: Nicholas M. Short, Sr. email: nmshort@epix.net

and

Jon Robinson email: Jon.W.Robinson.1@gsfc.nasa.gov

Webmaster: Bill Dickinson Jr. email: rstwebmaster@gsti.com

Web Production: Christiane Robinson, Terri Ho and Nannette Fekete

Updated: 1999.03.15.